by James M. Klas

In June of last year, faced with a global health and economic crisis unseen in generations, it was important to research and analyze the potential patterns and impacts of the pandemic and associated mitigation efforts on tribal economies. That the extraordinary crisis was occurring in the midst of an election year and the greatest surge in racial and social unrest in decades only added to the uncertainty. To assist tribal leaders, KlasRobinson Q.E.D. completed a white paper on the effects of the pandemic and associated mitigation efforts on tribal economies entitled: Healing Tribal Economies. The data and forecasts were updated in September of last year and the final update was published in February 2021. The following provides a summary of key forecasts from the February update to this paper.

We are now over a full year since the pandemic began in the U.S. Vaccines are now being distributed and the case and death rates have fallen significantly since the overwhelming peaks in December and January. The election has occurred and a new administration is in place, allowing for greater certainty in governmental actions going forward. Year-end figures for key economic measures are now available, although many more detailed statistics will not be released for weeks or months.

A smaller relief measure was passed late last year. There is a collective and reasonable sense that an end, if still several months away, is visible on the horizon.

This does not mean that either the pandemic or the economic crisis are finished as yet. Mutated versions of the virus that are more easily transmissible are becoming dominant. Despite the urgency, vaccinations will inevitably take more time, measured in months, not days or weeks. There is a race between vaccinations and the disease mutations that we may not win. The toll in Indian Country has been particularly severe. According to the CDC, Native Americans are the most likely of the racial/ethnic groups measured to get the disease. American Indian and Alaska Native populations are 1.8 times more likely than Non-Hispanic Whites to get COVID-19, four times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.6 times more likely to die from the disease. Given the current state of vaccinations, it is anticipated that the pandemic will substantially be under control, although by no means fully eradicated, by the end of June this year. Following that time, it is assumed that COVID-19 will cease to be a major determining factor in the economy, although the effects of its ravages and of the responses needed to control it will extend far beyond that date. However, the ongoing caseload and death rate of the virus beyond that time is no longer assumed to be an imminent driver of the economy.

Three overlapping phases to the crisis were originally identified: initial, transitional and recovery. The U.S. is now squarely in the midst of the transitional phase of the recovery, having moved beyond the initial scrambling efforts to respond to constantly worsening conditions and find ways to both sustain public health and sustain the economy. While the playbook has grown and become more stable, we are still actively combating the pandemic and have much work and risk remaining in front of us.

The recovery phase is expected to begin in or around September of 2021 and continue into early 2023. During the recovery phase, the transitional steps taken in preceding months will be further refined and made permanent. The most important aspect of this phase will be the end of direct, unpredictable and rapidly changing governmental intervention in exchange for stabilized and permanent policies upon which operators can rely for future planning.

Overall, the economic impact of the pandemic and associated mitigation efforts was generally less severe in 2020 than first feared, but heavy nevertheless. GDP was down 3.5 percent for 2020. The unemployment rate for 2020 averaged 8.1 percent. The consumer price index (CPI-U) for 2020 increased 1.4 percent. The clear policy decision to emphasize economic recovery as much as possible, even in the face of greater caseloads and death tolls, resulted in less severe economic impacts in the third and fourth quarters.

There are also signs of greater resilience in business and consumer attitudes and behavior than originally expected, suggesting faster recovery once the pandemic is finally tamed. Substantial, but by no means full, recovery across most sectors is expected for this year. By the end of 2022, most sectors are expected to have reached full recovery. However, certain sectors are still not forecast to reach full recovery until 2023.

During this period, new procedures, designs, products, pricing levels, staffing levels and market positioning developed during the transitional phase will stabilize and become a permanent part of each industry sector throughout Indian Country and the U.S. as a whole. Also during this period, new business ventures will begin to appear and grow, replacing lost businesses that were unable to survive the crisis and seeded in many cases by the very staff and investors of those same businesses. Not unlike a forest floor sprouting new growth after a fire, the economy will be boosted by new versions of old businesses and business models and by some new growth that is entirely different in character and focus.

There was a period of time this past spring when there were no Indian casinos open to the public anywhere in the country. By the beginning of July, nearly 82 percent of all Indian casinos had reopened to some degree. Unfortunately, the pace of reopenings slowed thereafter and several casinos that had reopened were forced to close again for two weeks or more due to new outbreaks. At year-end in 2020, 427 of the nation’s 489 Indian casinos were open, a ratio of 87.3 percent. For casinos that had closed one or more times but were open at year-end, the average length of time closed was 84.4 days, or 23 percent of the year. The median number of days closed was somewhat lower at 76 days. These counts do not include casinos that have remained closed throughout 2020 since their initial closures last year and have yet to reopen.

For the casinos that have been able to reopen, capacity constraints remain in place virtually across the board and the methods of achieving those constraints have become more flexible and more customer friendly. Mask requirements and plexiglass between seats at table games or between machines are being used to increase physical gaming capacity. Rather than turning off machines, the number of chairs on the gaming floor is being reduced to give the customer the ability to still gravitate toward favorite games. Many operations have reduced or even eliminated smoking areas to reduce reasons for customers to remove their masks.

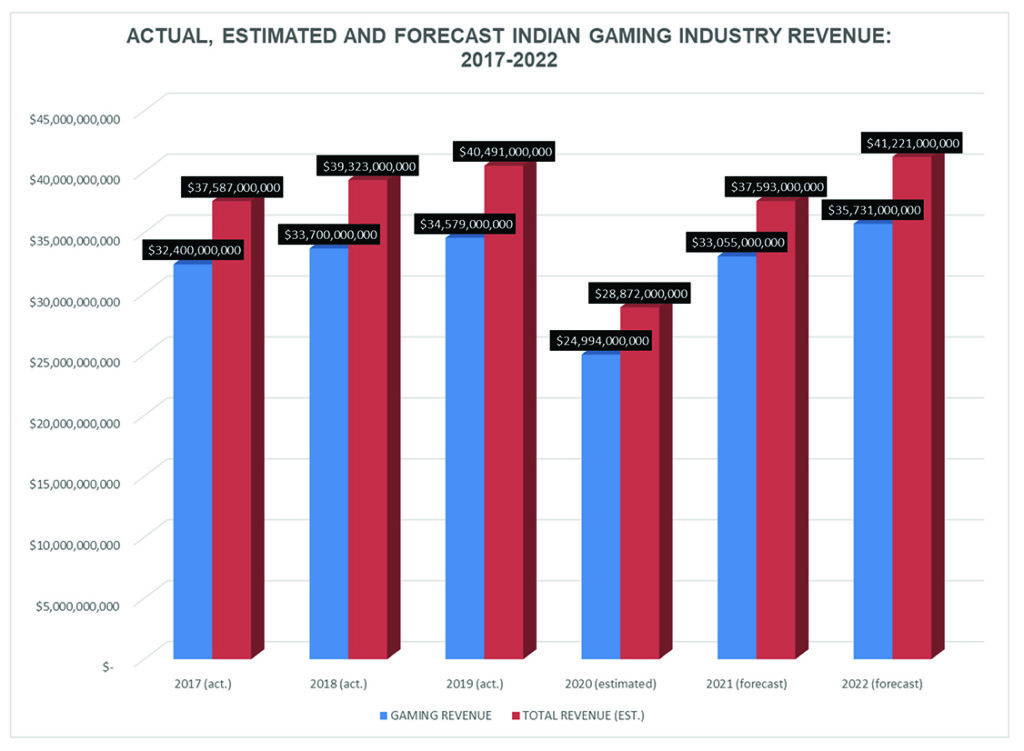

Based upon the information available on Indian casino performance in 2020, it is now estimated that gaming revenue declined 27.7 percent in 2020 and ancillary revenue at Indian casinos declined 34.4 percent, for an overall decline in total revenue at Indian casinos for 2020 of approximately 28.7 percent. For 2021, an increase in gaming revenue of 32.3 percent is forecasted and an increase in total revenue of 30.2 percent as recovery begins, still leaving the industry approximately seven percent below estimated 2019 levels. In 2022, substantial recovery is forecast to continue, with gaming revenue up 8.1 percent and total revenue up nearly 9.7 percent from 2021. By the end of 2022, the Indian gaming industry will have surpassed 2019 levels and already be showing new growth. This information is presented in Figure 1. Gaming revenue data for 2017, 2018 and 2019 are taken from NIGC statistics. All other figures are estimates and forecasts by KlasRobinson. Figure 2 below presents a listing of updated forecasts for various sectors of tribal economies across the country compared to those from the September update. The experience of individual tribes will vary depending upon local circumstances and actions that their leaders and the leaders in their surrounding counties and states take.

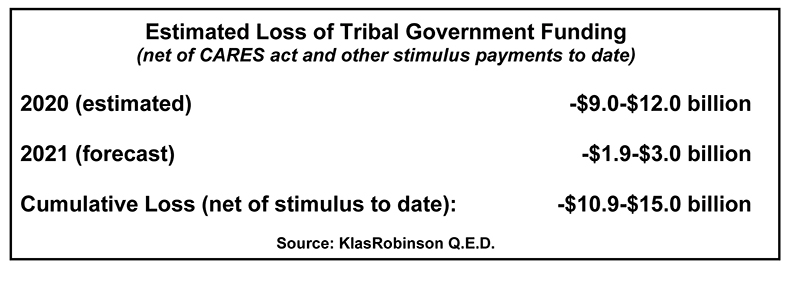

This final update applies year-end data and more in-depth analysis to generate estimates of the actual loss of government revenue to Indian tribes. Federal support has helped mitigate that decline to a degree, with $8 billion set aside in the original CARES act for tribal governments. However, the CARES act included significant restrictions on the uses of that funding that have reduced its benefits to Indian Country. It is estimated that the negative budgetary impact on tribal governments in 2020, after accounting for federal relief/stimulus efforts to date, equaled between $9 billion and $12 billion. For 2021, an additional negative budgetary impact on tribal governments of $1.9 to $3.0 billion is forecasted, for a cumulative shortfall of between $10.9 billion and $15.0 billion.

James M. Klas is Co-Founder and Principal of KlasRobinson Q.E.D., a national consulting firm specializing in the economic impact and feasibility of casinos, hotels and other related ancillary developments in Indian Country. He can be reached by calling (800) 475-8140 or email [email protected].