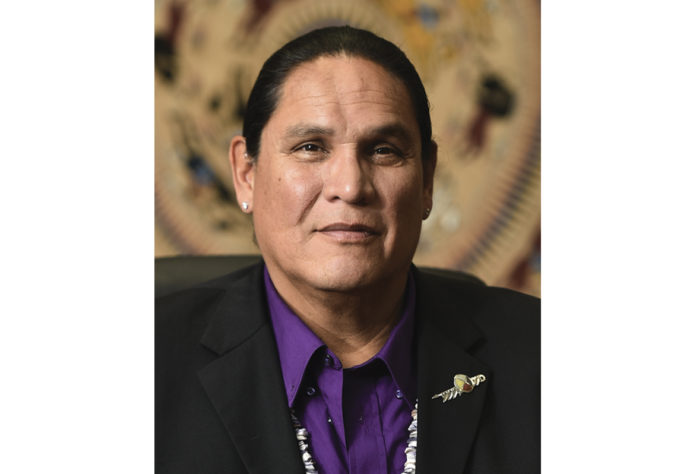

by Ernest L. Stevens, Jr.

Indian Country is celebrating a decades-long legal battle that affirms the ability of Native nations to engage in Indian gaming. On June 15, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe to conduct gaming on their lands.

The Indian Gaming Association has stood by the Texas tribes throughout this 30-year legal battle. The Indian Gaming Association, together with the National Congress of American Indians and the United South and Eastern Tribes, sponsored and filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court. Our brief contended that, under the Court’s 1987 California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians decision and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 (IGRA), the State of Texas has no authority regulate gaming on Indian lands that is not subject to a full prohibition against gaming.

The underlying facts and timeline involved in this case are truly unique and worth restating.

On February 25, 1987, the Supreme Court issued the historic Cabazon decision, affirming the sovereign right of all federally recognized Indian tribes to conduct gaming on their lands. The Court made a clear distinction between state laws that wholly prohibit gaming and laws that permit some forms of gaming, subject to limitations – which it deemed regulatory.

On August 18, 1987, Congress enacted the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and Alabama-Coushatta Indian Tribes Restoration Act, restoring the governmental status of the two tribes. The Restoration Act, passed into law just months after the Cabazon decision, adopted the Cabazon Court’s criminal/prohibitory versus civil/regulatory approach.

A little more than one year later, on October 17, 1988, Congress enacted IGRA, effectively codifying much of what the Court held in Cabazon and setting forth a three-tiered regulatory structure for tribal government-operated gaming.

In 1993, relying on IGRA and Cabazon, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo opened its Speaking Rock casino after the National Indian Gaming Commission approved the tribe’s gaming ordinance pursuant to IGRA. The tribes and the State of Texas have been mired in litigation since.

In 1994, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals initially ruled that the Restoration Act of 1987 withstood the later enactment of IGRA, siding with Texas in finding that its gaming laws apply on Indian lands. This decision led to confusion, uncertainty, and more than 25 years of litigation.

The current case before the Supreme Court stems from the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo’s reopening of its Speaking Rock casino in 2016. The tribe’s operation was limited to Class II gaming that included both paper and electronic bingo. The state brought suit to again shut down the tribe’s gaming operation, citing the 1994 Fifth Circuit decision that the Restoration Act subjects the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo to all State of Texas’ gaming laws.

The lower courts sided with Texas and enjoined the tribe’s bingo operations, and the U.S. Supreme Court finally agreed to review the interplay between the 1987 Texas Tribes Restoration Act, the Cabazon decision, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

The Supreme Court held that the 1987 Restoration Act “did not subject the tribe to all Texas laws that ‘prohibit or regulate’ gaming. It did not subject the tribe to all laws that ‘govern the regulation of gambling.’ Instead, Congress banned on tribal lands only those gaming activities ‘prohibited’ by Texas, and it did not provide for state ‘regulatory jurisdiction’ over tribal gaming.”

The 5-4 majority, authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, reasoned that “at the time Congress adopted the Restoration Act, Cabazon was not only a relevant precedent; it was the precedent.” The majority further linked Cabazon to the present case, noting the Cabazon Court drew a “sharp line between the terms prohibitory and regulatory and held that state bingo laws very much like the ones now before us qualified as regulatory rather than prohibitory in nature. We do not see how we might fairly read the terms of the Restoration Act except in the same light.”

The Indian Gaming Association lauds the Court’s decision as an incredible victory for Indian gaming, tribal self-determination, and most importantly for the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe.

The Supreme Court noted that the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo’s Speaking Rock casino accounted for 60 percent of the tribal government’s operating budget, which supports “significant educational, governmental, and charitable initiatives.” When Speaking Rock closed, the Ysleta del Sur’s unemployment rate rose from 3 to 28 percent.

These Native nations can now join the more than 200 other Indian tribes engaged in gaming to improve their communities. For much of the past half century, Native nations have used Indian gaming to rebuild their communities. Tribes are using revenue generated from Indian gaming to improve basic health care, education, public safety, and housing services on Indian lands. Indian gaming operations generate more than 300,000 direct jobs and serve as economic anchors for community development and entrepreneurship.

Ernest L. Stevens, Jr. is Chairman of the Indian Gaming Association. He can be reached by calling (202) 546-7711 or visit www.indiangaming.org.